By Emily Pelland

Minutes before 7 o’clock on a Wednesday evening, Erricka Bridgeford arrives at the 1600 block of Moreland Avenue in Baltimore, Maryland, on a cool spring night.

Brick rowhouses line the neighborhood of Sandtown-Winchester in West Baltimore City. Billie Holiday, Cab Calloway and Thurgood Marshall hailed from here. It is also the home of the late Freddie Gray, whose death fueled protests in April 2015.

Residents live in rowhouses, some vacant with boarded-up windows and doors. All of the homes are in need of major repair. Some have sunken roofs. Children play on front porches with missing boards. Broken glass is strewn across the ground.

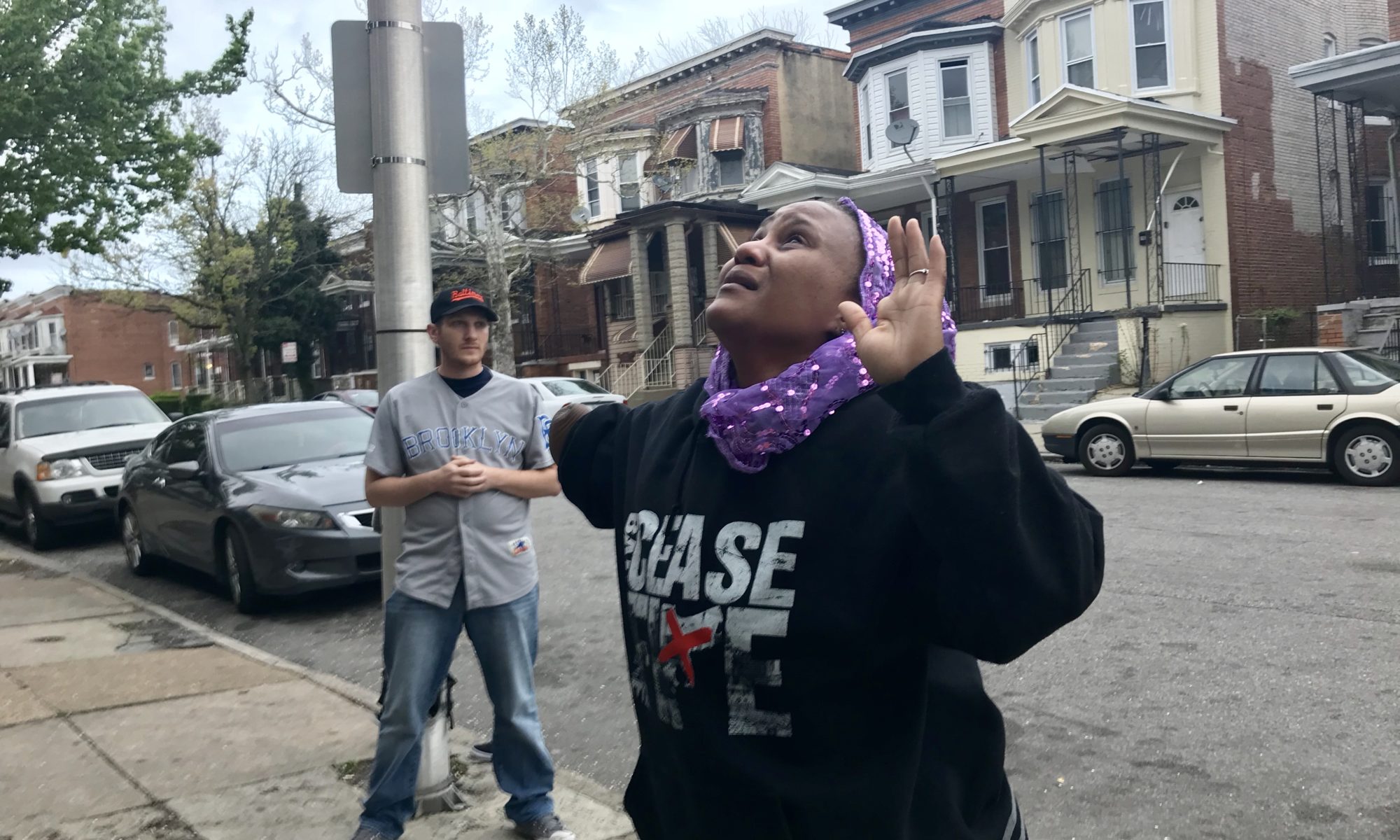

Bridgeford lights a bundle of dried sage leaves tied together with string. She gracefully waves the smoky scent along the sidewalk, up and down a tree, and in the air as she walks around the block. She wears a black hoodie with the words, “Baltimore Ceasefire” and a purple scarf with sequins.

A group of four other people accompany Bridgeford, some also wearing Baltimore Ceasefire hoodies.

Residents standing in front of their homes are curious

“We’re just trying to put some love in the neighborhood, because Mac got killed right here,” she says with a slight tremble in her voice.

Dominic “Mac” Smith was shot and killed earlier this month. He was 27. Bridgfords is performing a sacred ceremony for Mac.

As of April 27, 2018, Baltimore lost 87 residents to homicide, 79 are a result of gun violence.

Bridgeford makes it a point to visit every location of recently reported homicides in Baltimore City.

“We don’t want people thinking we don’t care when something horrible happens,” Bridgeford says. “I wanted someone to care when it was my brother.”

Her brother was killed in 2007. So were two other cousins in 2005 and 2015. All were murdered by guns. Her neighborhood in West Baltimore has one of the highest rates of homicide in the city. Bridgeford has grown up among the violence since she was 12.

She works as a peacemaker, mediator and activist. She is credited as one of the driving forces to repeal the death penalty in Maryland and The Baltimore Sun named her the 2018 Marylander of the Year. She is also the founder and co-organizer of Baltimore Ceasefire 365. The group goes door to door with a message: “Nobody kill anybody.”

The purpose of the Ceasefire is to get people to have conversations about the murders in the city and to allow residents to connect with volunteers who can direct them to resources such as basic health care for victims recovering from the trauma of living in a city with a high homicide rate.

Locals debate the effectiveness of the Ceasefire weekends, though Bridgeford says she’s glad that people are talking to one another about how to deal with the violence. She says that murder is an epidemic that will spread if communities don’t work toward more peaceful change in the near future.

“Those are the conversations we need to be having. Because at some point we’ll get tired of those conversations, and it moves us to action,” she says.” And so this is one of our ways to do action all together as one big city.”

Bridgeford’s activism was shaped by her family. Her father is a former Black Panther and encouraged his daughter to confront injustices when they arise. Initially, Bridgeford wasn’t thinking of turning her activism into a career.

“When you deal with that kind of pain consistently, for me, it was either going to swallow me up whole, or I had to do something about it,” she says.

“I just started being involved and doing things. And so before I knew it, that got labeled ‘she’s an activist,’ and I was like, ‘Okay, I guess that’s what that means!’”

Part of that work means walking up and down the streets of Baltimore and performing her sacred ceremonies “to pour light and love” into what were once crime scenes. Bridgeford believes in the power of energy, and she wants to get rid of “all these dark holes all over the city.”

On this particular night, Bridgeford is performing her ceremony when one of the neighbors opens his door.

“I’ve seen you on TV,” he says. “Thank you for what you’re doing.”

Occasionally she lights the bundle of sage clenched in her arm, and a plume of thick smoke drifts into the sky.

“People get killed here all the time,” she says. “You can just ride through any neighborhood in Baltimore [and] see that if somebody had to live like this every single day, they would be under a level of stress that you probably can’t imagine.”

The sight of a teenage girl sitting on one of the porches breaks the solemness of the ceremony. Bridgeford screams in excitement. This is a friend’s daughter, and Bridgeford didn’t know the family lived on this street. Bridgeford’s exuberant laughter echoes against the brick, and she briefly embraces the girl and promises to return once she finishes the sacred ceremony.

As she descends the steps, Bridgeford’s body stiffens and her eyes water. Once again, she continues along the the sidewalk, stopping to give each tree the scent of sage.

Tears begin to fill her eyes as she stops in front of house number 1622, the site of Dominic “Mac” Smith’s murder.

Another woman in a Ceasefire hoodie also spreads the smoke of sage, tracing it along Bridgeford’s body in front of the house.

Soon, Bridgeford begins to chant, “Let there be light. Love and light. Let there be peace.”

She gets down on her hands and knees. Her hand rubs the concrete. She cries more.

“Whatever is in this neighborhood, let there be peace,” she wails. “Let there be joy. Let there be awakening. Let there be healing. Let there be a knowledge of worthiness, of life. Whatever has taken hold of this community, we stand with light. We stand with love. This is what they deserve.”

The group disperses, and Bridgeford walks back to her friend’s house and happily changes her mood. She laughs and hugs each person who comes out of the house. Their animated voices fill the space under the setting sun.

“Doing a lot of the things that I do actually helps me have peace,” she says. “And so right now when I go to every location where somebody has been murdered and do what we call a sacred space ritual, that feeds me in a very weird kind of way.

“Just because I know that I am doing something about murder. Like murder doesn’t have the last say.”

Bridgeford expects to perform another sacred ceremony the following evening.